Medical care at sea has been around since the humans first left the shore. The larger the crew and the higher the value of the vessel, the greater the need for medicine at sea. From the beginning of sea-going travel, the role of an onboard medical officer was established as a necessity. And the thousands of those practicing medicine at sea with a long history of management of disease and injury were primarily self-trained medical officers. The label “Ships Surgeon” is an English term describing a person who is responsible for medical care afloat and a few of these medical officers’ names have been recorded. History tells us that it was Julius Caesar who elevated “medics” to the officer ranks on land and sea in the first century BC. They have maintained that status to this day. Somewhere along the way, the title of Ships Surgeon entered the vocabulary. Their primary duty was to maintain the health of crew members in peace and war. By the 20th century, the United States Coast Guard had developed standards and credentials to become a licensed ship surgeon. When I became licensed as a ship surgeon in 1985, five documents were required. Upon presenting myself and my documentation to the USCG station in Alameda, California, the resident official told me there was no such license. I ask him to check the reference prompting him to leave the desk and research my request. He returned shaking his head and saying there certainly was such a licence even though in his forty years had never issued one and asked for my documentation. To become a Ships Surgeon, one must have proof of an unrestricted license to practice medicine and surgery in one of the fifty states, a letter from a shipping company with an intent to hire me, and three notarized statements from physicians that I was sober. These statements were important since the ship’s Surgeon had access to the ship’s supply of alcohol and opium. The Coast Guard no longer dispenses this license and since I qualified forty years ago this summer I am perhaps the only USCG Ships left standing,

Edward Cree’s painting of the attack on Canton was one of many battles during the Opium Wars forcing the Chinese to buy British Opium. Dr. Cree was a 19th-century ships surgeon who left behind a vivid description in words and paintings of life at sea. During battles like the one above the wounded accumulated and brought to the ship’s operating theatre, the cockpit whose floor and walls are painted red to hide the amount of blood spilled by wounds and amputations. Sickbay was below decks this space unlighted and unventilated below the waterline. Few who entered the sick bay emerged alive, dying in one another’s feces, vomit, and blood. Simple wounds became infected, leading to amputations and death from infection. Sailors and Marines with open chest and abdominal wounds were untreatable in Dr. Edward Cree’s surgery and simply made more comfortable on their way to certain death. Queen Victoria needed opium to pay for the British Navy, which ruled the seas in the 19th century. Much of England’s ships, both military and merchant were built on the backs of millions of opium-addicted Chinese. Victoria was and continues to be, history’s biggest drug dealer.

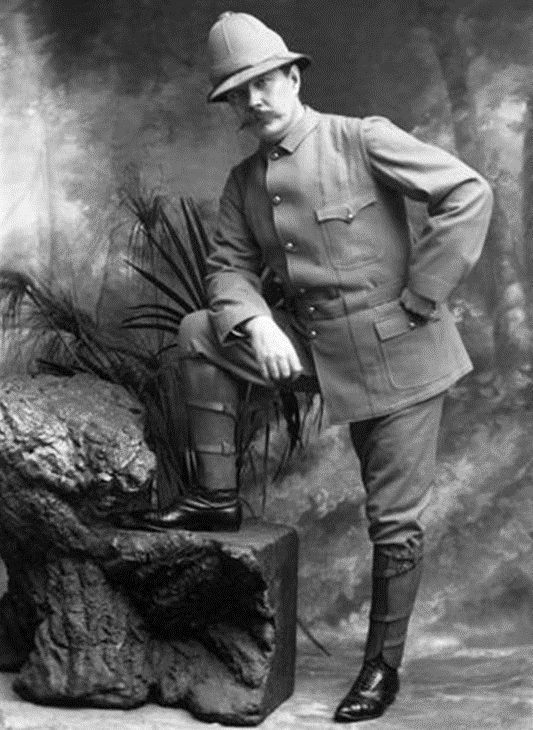

The famous author in a British Officer’s field surgeon uniform in the Boer War South Africa where he volunteered and paid the cost of his entire mobile surgical hospital. Image from Doyle Family Estate

This Ships Surgeon is well known to many as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle who after spending years sailing with the British and other European Merchant Marine became addicted to cocaine and opium. His famous character Sherlock Holmes was a frequent user of both drugs in his stories. The fictional Sherlock Holmes solved many of his cases due to his amazing powers of observation, an important skill of any medical officer, especially when operating alone. The alcoholic Ships Surgeon, Thomas Huggan aboard “The Bounty” was the primary cause of the famous mutiny while the Ships Surgeon, Theo Morell, Hitler’s personal physician was likely the cause of many of Hitler’s disastrous decisions late in World War II. These stories and others are found in “Medicine at Sea”.